Malaga Island: A Story Best Left Untold had its genesis in a classroom. A student at The Salt Institute for Documentary Studies, where both Kate Philbrick and I taught, came into my radio class one day and said “Have you heard about this island near Phippsburg? It’s crazy. Malaga Island. The people who lived there a hundred years ago were the concubines of sea captains and their offspring!” Needless to say, everyone in the class was surprised and dubious.

The student, Matt Largey, went on to say that he heard the islanders lived in caves and were eventually evicted by the state (the eviction is the only true part of that story). Matt told us he tried to talk to people in Phippsburg about the story but no one was willing to be interviewed and those that did talk to him only spoke off the record about these “Well, what I heard was…” stories. Frustrated that he couldn’t get anywhere with his research, he gave up and moved on.

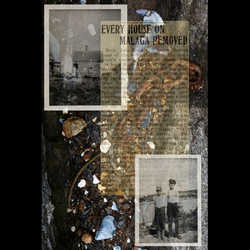

A couple of years later, the Portland Press Herald published an article about an upcoming NAACP event for Black History Month on Malaga. The article detailed Malaga’s history, including the myths Matt discovered, and so much more – the context of eugenics, racism, economics, and tourism; the actions taken by the state; and photos of islanders. Missing, oddly, were the voices of descendants. But, this was enough for Kate and I to take deep interest in the story. With permission from Matt, who is now a successful public radio reporter, we began our research.

At the beginning, in 2006, we were told again and again to expect resistance from Malaga Island descendants. “They won’t talk to you,” we heard. Oddly, though, what we discovered was that non-descendants were the most reticent to speak to us. One resident of Phippsburg not related to anyone on the island who was affiliated with Phippsburg Historical Society shook her finger at me and said “I don’t trust you.” Another left me a message on my answering machine declining to be interviewed. “That’s a story best left untold,” she declared. Then she hung up.

Descendants, on the other hand, while not always eager to talk and be photographed, were generally quite the opposite of what we were told to expect. They graciously welcomed us into their homes and opened up to us in ways we never anticipated. In fact, we interviewed one descendent three times! All told, a dozen or so descendants and their families agreed to be interviewed and have their pictures taken. And, eventually, we found a handful of non-descendants willing to speak with us. To all of them, we are grateful.

Though Kate and I did a considerable amount of investigation, we were greatly assisted by several researchers, academics, and journalists all of whom appear in the documentary. We stand on their shoulders and can’t thank them enough for their generosity and assistance.

All told, in the three years of part-time work on this project, I recorded approximately fifty hours of interviews, Kate took thousands of photos, and we spent hours in libraries and archives reading and scanning documents and newspaper reports.

Our project opened in February of 2009 in the gallery at the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies. An audience of some two hundred visited the gallery on opening night. An overflow crowd stayed to listen to the entire hour-long documentary.

Malaga Island: A Story Best Left Untold has aired several times on public radio stations in Maine and on a dozen or so stations around the country. We were awarded “First Place” for public affairs reporting by the Maine Association of Broadcasters. And, our work was included in the Maine State Museum’s year-long exhibit “Malaga Island: Fragmented Lives” in Augusta in 2012.

For Kate Philbrick and myself, we are incredibly thankful for your interest in this story. Please tell others.

—Rob Rosenthal